Photo by Hédi Benyounes

This is part 2 of a 3-part series on Mass Incarceration, and it picks up right where I left off in part 1. If you haven’t read that post yet and aren’t aware of why I think it’s a humanitarian crisis of epic proportions in America, go back and check out that post now! But not only is it such a massive crisis, I think it’s one that disproportionately affects People of Color.

THE ENTANGLEMENT WITH RACISM

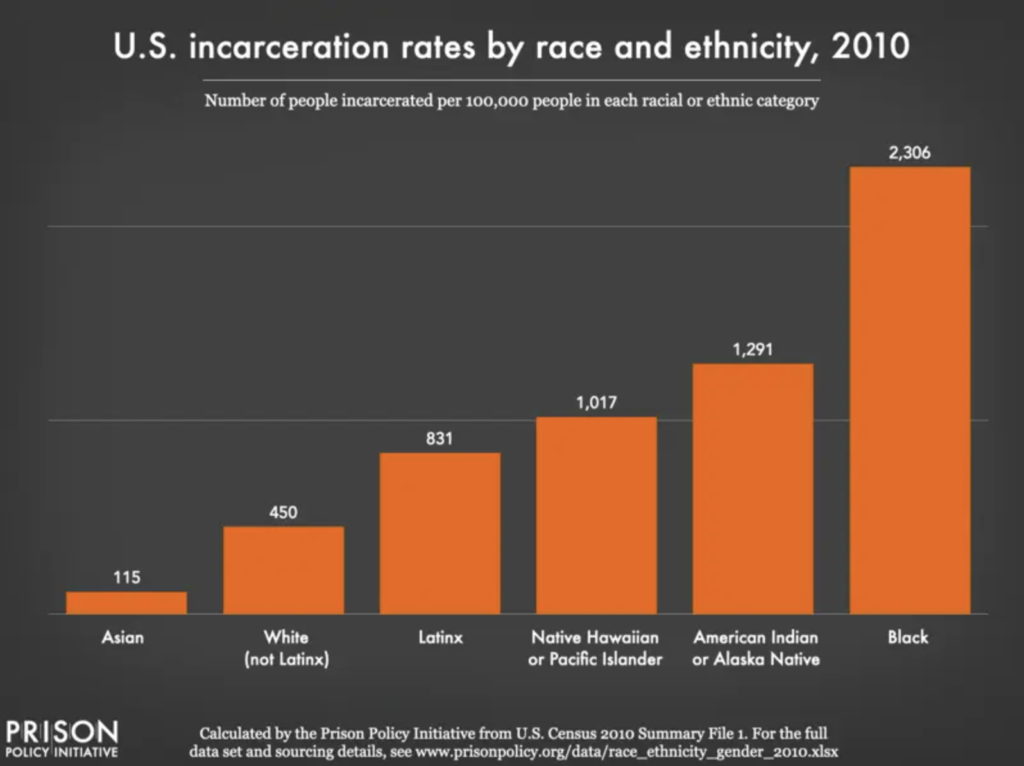

I have to admit, I’m often surprised by those who push back against the notion that races are affected differently, especially when it involves incarceration. I mean, Black people account for 39.6% of all incarcerated but only 12.6% of the overall population while White people only account for 50.3% of all incarcerated but represent 72.4% of the nation’s population. And as illustrated in the image below, it’s not just Black people who are disproportionately affected.

Many highlight America’s long history of systemic and structural racism as just one of the many contributing factors, and I would agree. Perhaps another is implicit racial bias, although maybe that’s just one result from such racism. I get that people often have good intentions. And I certainly understand people’s deeply rooted desire to want to consciously believe in equality. But how do we not all agree that our society has been socialized from the very beginning to view White people as harmless, innocent, and proper while perceiving People of Color as dangerous, inferior, and threatening? From the White Lion’s arrival in 1609, to the Declaration of Independence declaring all men to be created equal but intentionally restricting some men from that equality, to the Civil War and the South’s desire for an economy that reliant on slave labor, to the Civil Rights Movement and people demanding equality they were already entitled, all the way to the civil unrest of 2020 where people can’t agree on whose lives matter… to me, it’s clear. Racist ideas and policies are still present today just as they have been since the very beginning. It’s ingrained in our culture. It’s in the smog we all breathe. Like a friend said recently, it is the smog we breathe. It’s inescapable.

So how is it possible to deny that, as much as we all may not want to believe, it’s possible we have subconscious beliefs when it comes to race? And is it possible that those beliefs might offer insight as to why law enforcement officers are able to peacefully engage with and apprehend particularly violent White men responsible for heinous murders while many Black and Brown people are not so fortunate. Philando Castille was shot and killed by police while complying with orders. Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old, was shot within seconds by an officer who thought he was a large and threatening man. Walter Scott was shot in the back while running away. Stephon Clark, Botham Jean, Alton Sterling… The list is tragically too long and only seems to get longer as time passes.

The biased view of Black and Brown people as more threatening doesn’t just end with more arrests for People of Color. It also shows up in the sentences they receive, which are often lengthier than White people who are sentenced for similar crimes. The ACLU released a report in 2014 that found sentences imposed on Black men in federal prison were nearly 20% longer than those of White men convicted of similar crimes. Some may wonder if such sentences are because of potential prior histories for violent offenses by Black offenders, but another similar report released in 2017 by the U.S. Sentencing Commission declared that Black male offenders received sentences 19.1% longer than similarly situated White men even when offenders had similar backgrounds for violent offenses.

These differences in sentencing have also been observed in juveniles, as Black and Brown children are often handed different punishments than White children for being viewed as more threatening and responsible for their behavior. According to the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, data from 2018 found that nearly 40% of Black juveniles charged with weapons offenses had their cases adjudicated (meaning they were deemed responsible for their actions, most likely by a juvenile judge) and 13% were placed in a secure facility away from their home while, in contrast, only 27% of White children facing the very same charges had their cases adjudicated and only 5% were placed in such a facility. And while only 14% of the nation’s youth (18-years-old or younger) are Black, they account for 66% of the entire nation’s robbery offenses! It’s not surprising to know adolescents who have been arrested often have lower graduation rates, higher rates of recidivism, and more troubles finding a job.

For these reasons and more, many are becoming increasingly concerned with the emergence of the school-to-prison pipeline, which is the term commonly used to describe the alarming number of Black and Brown children being funneled (both directly and indirectly) from schools to carceral facilities. In the words of Ijeoma Oluo, Black and Brown children seemed to be being groomed for incarceration even from the disparate punishment for infractions in school. She cites how Black students make up only 16% of school populations but represent 31% of suspensions and 40% of expulsions. Black students are also 3.5x more likely to be suspended than White students, and 70% of arrests in schools or referrals to law enforcement involve Black students. All of these worrisome statistics illustrate how it’s easy to see the seeds being planted in the minds of today’s Black and Brown youth that they are likely to be sent down a path of incarceration at some point in their life. But I think the prevalence of juvenile adjudication and disparities in sentence lengths beg an interesting question.

How many convictions might be avoided if an alleged offender chooses to go to trial?

I’ve been unable to shake this thought once I learned that approximately 97% of all criminal cases involve a plea bargain and never go to trial! But as alarming as that number was to me, I suppose it began to make sense once I realized there are only an estimated 2,300 elected prosecutors in the entire country. And shockingly, 95% of them are white men, 83% are men, and only 1% are Women of Color!

In my home state of Georgia there are a total of 49 district attorneys. But in 2017 alone there were a total of 51,967 arrests. Does that mean over 50,000 of the cases involved plea bargains? And if so, how likely is it that every single person who took a plea deal was actually guilty? Not very. While it may not be the intention, these exceptionally high rates for plea bargains can give the appearance that, simply by making an arrest, law enforcement officers are actually the judge, the jury, and, all-too-often, the executioner. After all, George Floyd was initially detained for allegedly using a counterfeit $20 bill, and that mere accusation resulted in him losing his life.

But suppose Floyd had been arrested safely and civilly, would he have accepted a plea deal for the alleged offense? Shamefully, we’ll never know. But what we do know is there are too many people being arrested and admitting guilt for things that they perhaps would never be found guilty of if they were willing to go to trial. Tragically, so many don’t see that as a safe or available option, and that’s just one of the many things I would love to see change.

And that’s what part 3 will be about, tangible ideas and policies that can have an immediate and long-term effect. Stay tuned!