Good for Mississippi for finally addressing their state flag.

Although, the debate isn’t new to them. A vote back in 2001 saw 65% of voters opt to keep the existing flag. The decision even made one former state commander of the Sons of Confederate Veterans proud. He admitted the KKK and others have used the Confederate battle flag to promote hate and instill fear, but he also said the flag was important to his family and heritage. He said the battle flag’s cross was emblematic of “courage, pride, and honor” and he hoped the outcome would “turn the tide on the cultural cleansing in our country.”

Oh, the irony of someone committed to popularizing the narrative of Confederate veterans also being fearful of cultural genocide. Maybe he was referring to South Carolina’s removal of the battle flag from their capitol building the year before. Or maybe he was talking about Georgia’s controversial decision months prior to change its state flag.

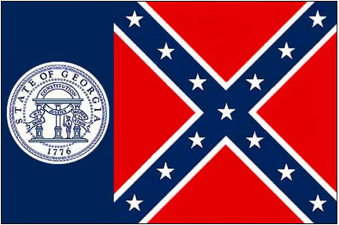

I was in high school in 2001 and wasn’t really aware of the controversy surrounding how Governor Roy Barnes changed the flag. But while I didn’t understand all of the flag’s history, I still remember opposing it. Unlike Mississippi’s flag which displays a small battle flag, Georgia dedicated two-thirds of the flag to it. To me, the symbol was a reminder of segregation and hatred, of racism and white supremacy. But not everyone saw it that way. Some saw, and still see, it as a symbol of history and heritage, as something to be kept and revered.

Just because it was a part of history, did that mean it had to be glorified and exalted? Did simply being an old emblem prevent it from also being inappropriate and something to denounce?

I’m older now and know a little more about Georgia’s flag history. But I must admit I’ve learned some things recently that still shock me, things about the infamous flag I grew up with. It may surprise some but that flag (Fig. A) was actually Georgia’s 5th official one in its history and was adopted on July 1st, in 1956.

Many Georgians are familiar with the flag. It’s known as the one with the large Confederate battle flag, an emotionally and racially charged emblem. I never understood why it was something to memorialize. Some claim this particular flag was adopted to celebrate the upcoming 100-year anniversary of the Civil War. But that centennial anniversary was still five years away, and that argument didn’t start to get popular until after the flag’s adoption.

A more plausible explanation for the flag was that it served as a reminder of the support for segregation and white supremacy. After all, the flag was revealed very shortly after Supreme Court decisions related to Brown v Board, calling for schools to integrate and do so quickly. Georgia was one of numerous states that vehemently opposed school integration, and this new flag was designed by John Sammons Bell, a segregationist, who is attributed with saying it was Georgia’s way of letting the NAACP and the rest of the nation know that white Georgians, once willing to die to protect slavery, were also willing to die to protect segregation.

Is the flag historically relevant to you? Do you see it as a symbol of hatred? Or something else?

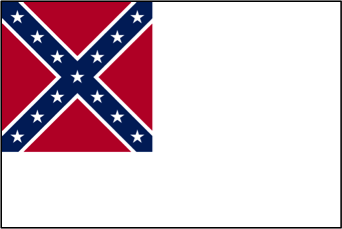

Some refer to the Confederate battle flag as the “stars and bars” but that’s actually not accurate. The “stars and bars” refers to a different flag (Fig. B) that served as the 1st official flag for the Confederate States of America between 1861 and 1863. The number of stars gradually grew from 7 to 13 as more states seceded but the overall design remained the same.

The name “stars and bars” was likely meant to oppose the name “stars and stripes” flag, used to describe the traditional American flag many are familiar with. But those flags look similar and it was tough to distinguish them during the war. The Confederacy needed a new flag, and that’s where the battle flag comes in, since it was already a well-known and liked symbol. So an all-white banner was created with the battle flag in the top-left corner, and that became the 2nd official flag (Fig. C) for the Confederate States of America from 1863 through 1865.

Eventually, a 3rd and final flag was adopted by the Confederacy because the 2nd flag was mostly white and could be confused for a flag of surrender. Regardless, by 1863, the battle flag on its own had become a prominent symbol in the South and one with a very specific meaning, one that still generates emotions to this day. And while many see it is a symbol of heritage, they often leave out something very important.

It was those Confederate States of America who opted to withdraw from and actually go to war with this country, the United States, in order to protect and preserve slavery and the right to own other humans like livestock. While it may not be technically accurate, for all intents and purposes, they were an “independent republic” who opposed this country under this banner.

Why is that flag and the heritage that it represents something to celebrate?

The argument over Georgia’s 5th flag had been underway for quite some time when Roy Barnes decided to change the flag, which he seemed to do almost unknowingly to many. And in 2001, just like that, the state had its 6th flag (Fig. D).

Many were unhappy the flag, not just for its look but because it was adopted without a public vote. That’s a very contentious issue, one even Mississippi’s Governor Tate Reeves acknowledged by saying their new flag should only come at the hands of a public vote. For Barnes, it ultimately meant his demise, and incoming Governor Sonny Perdue said he’d right the wrong. He called for legislators to decide between Barnes’ flag or yet another new one. And in 2003, Georgia adopted its 7th flag (Fig. E).

Does that flag look familiar? It should. It is literally the official “stars and bars” flag (Fig. B), which was the 1st official flag for the Confederate States of America don’t forget, with Georgia’s state seal inside the stars.

Why choose to copy the banner that flew for two years representing the Confederacy as they fought to protect slavery? Was this any better? Or was it just the better of two terrible options?

I must admit that even I didn’t discover this until fairly recently, and I wonder how many others are still unaware. I also wondered how many were actually aware when the flag was adopted. To my surprise, some people were upset back in 2003, but it wasn’t who I expected. And much of the anger didn’t even focus on this new flag. It still stemmed from the retirement of the flag with the battle symbol back in 2001. It’s worth noting this 7th flag was eventually passed by a public vote, but that ballot did not give voters the option to return to the 5th flag, which Governor Perdue had initially promised. And a representative for the Sons of Confederate Veterans echoed a similar sentiment to the one from Mississippi in 2001 by saying the battle flag is honorable and the most recognizable Southern symbol there is, and even went on to say we would be “like a people without a country if they take away all of our heritage.”

A people without a country? Did he not celebrate being a member of this country, the United States of America, more than the Confederate States of America? How does replacing the state flag with the first official flag of that other country take away his heritage?

It’s hard to imagine a representative for the Sons of Confederate Veterans not knowing that was the 1st official Confederate flag. Which means he was probably more concerned by others not recognizing this new flag as one used by the South during the Civil War era. And even if others do know the flag, they still probably didn’t immediately link it to neo-Nazis and the KKK.

As I said, this was a recent discovery, and I was relieved to learn there were some who did oppose the flag at the time. But it’s almost as though they were willing to concede the decision because many wouldn’t be so quick to recognize the new flag. One senator at the time wasn’t prepared to call it a major victory but simply something he could live with

Was this 7th flag acceptable because people didn’t widely associate it with hate? Was its true origin and meaning to be ignored just because most simply weren’t aware of it? Why did, and do, many insist on using symbols linked to hate and racism in the name of preserving heritage?

Nothing says Confederate flags must be flown at government buildings to be remembered. People can hang them in homes or yards as reminders of their heritage. And in fact, many do just that. Perhaps it’s why, if I’m honest, I struggle mightily with this argument of preserving the Confederacy’s history and heritage. And based on the recent influx of debates over Confederate monuments and memorials, I’m not alone. I wish someone could help me understand.

First, I’m not proposing we erase or ignore our history. I’ve had several conversations lately about Confederate monuments, and my stance is not to remove all of them with the intention of acting like nothing ever happened. Rather, where possible, I would like to see them modified to more accurately and thoroughly depict the history they are intended to preserve.

One example involves a statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest at the entrance of a cemetery in Rome, GA. It has garnered much attention lately, and I took a recent trip to check it out, to see its inscriptions. One quote etched in it was from General Beauregard and read as follows:

“Forrest’s capacity for war seemed only to be limited by the opportunities for its display.”

Implication being, he was a warrior who shamefully wasn’t given more opportunities to fight, disregarding the cause he actually fought for. Monuments with inscriptions like these, in my opinion, only serve to laud and glorify people like Forrest without referencing their support for slavery and oppression. What if the monument was modified to have an inscription that reads:

“Forrest was a slave owner and skilled rebel general who is attributed with being responsible for the murders of almost 300 prisoners of war, mostly black, at Fort Pillow, and he was nominated as the first grand Wizard of the KKK. He fought against this country on behalf of the rebellious Confederate States of America in support of preserving and protecting slavery.”

I’d support that. It gives more detail to what Forrest actually represented and calls attention to the history we don’t want to repeat, the history we are to learn from. But without something like that, the true significance of history is lost. Notice that I didn’t say this nation’s history because these monuments salute those who literally defied and fought against this country. That makes it all the more shocking to know there are almost 800 monuments (more than 300 in GA, VA, and NC alone) honoring the Confederate States of America.

Why are there not more monuments honoring the Union who fought to preserve this country? For those who actually fought for equality and freedom? Why are there not more monuments for Civil Rights leaders?

In addition to not overlooking the messaging and cause of the Confederacy, we can’t overlook the actual timing of when these monuments were erected. For instance, the statue of Forrest in Rome was revealed in 1908, less than two years after the Atlanta Race Riot of 1906. The timing indicates that it wasn’t just a tribute to Forrest, it was a reminder of the South’s continued endorsement of slavery and segregation. And many monuments like this one are fairly new. In the 1960s, in reaction to the passage of the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act, Texas installed 27 Confederate monuments dedicated to Confederate soldiers who had fought against “the federal enemy” while at least 30 of Tennessee’s more than 100 Confederate monuments were installed after 1976.

What does it say that these monuments were being constructed and revealed during Jim Crow and the Civil Rights era? Why were we still erecting tributes hailing the Confederacy as heroic?

Even if you don’t consider the monuments as praising those who fought for the Confederacy, I’m fairly confident that their mere existence, without the appropriate history to go along with them, has resulted in you knowing more about who fought for the Confederacy than the Union.

How many Union generals can you name? Even if I include Lincoln, off the top of my head I can honestly only name Ulysses S. Grant and General Sherman. And I know Sherman because I’ve heard about how he burned Atlanta for my entire life. So that’s three. How many did you get?

Now, how many Confederate generals can you name? I can name Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, Nathan Bedford Forrest, Beauregard, and Bragg before I even start to slow down. That’s six. How many did you get? Was it more than the Union?

Now, consider this. In the last 100 years, the U.S. has fought in WWI, WWII, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, and the most recent War in Afghanistan. How many of those generals can you name? I can only name Patton, but I honestly don’t even know what war he’s associated with. How many did you get? Was it as many as the Civil War? Why is it vastly easier to name Confederate generals but we don’t discuss or know the details of that war?

The Civil War ended 150 years ago, and we’re still debating how people should have the freedom to celebrate such a dark time in history. Can you imagine if Germans wanted to erect a monument to honor Adolf Hitler and commemorate their pride of German heritage? Or if a wealthy German philanthropist wanted to develop an outdoor park called Hitler Plaza with a plaque at the entrance declaring Hitler “a skilled leader of his country and one who fought valiantly for his cause”? It would never happen. Germany even banned the Hitler salute and swastika as hate speech. Meanwhile, here in America, the ACLU fought to protect self-identified neo-Nazis and KKK members so they could put their hate on full display for all to see in Charlottesville, and we know how that ended. Even South African banned the apartheid era flag for being a vivid symbol of white supremacy that immortalizes the era of racial segregation and oppression. But here in America, we debate for years not just about people’s rights to own the flags but if they’re to be displayed on government buildings out of pride.

Pride for what?

That’s an honest question, by the way. We put all this emphasis on how history is being ignored, but we haven’t been honest with ourselves for a long time when it comes to that very history. Not everyone even agrees that the cause of the Civil War was slavery! And others imply the North was a hero who fought for equality. That’s not entirely true, either. Lincoln himself admitted he didn’t support equality and endorsed sending freed slaves to another country after the war. Why can’t we have conversations like those to examine and learn from our history?

All that to say, if you think simply removing monuments denies history and heritage, I would argue that allowing them to remain as they are isn’t doing anything to help people see the whole picture or admit the error of our ways so we don’t replicate those same mistakes. And it’s not truthful to say the primary purpose of these monuments has been to honor fallen soldiers. That lie only serves to perpetuate the Lost Cause narrative and doesn’t address the inaccuracies.

Yes, we have an opportunity to learn from the past and can use these monuments as teachable moments. But can we agree the monuments in their current form aren’t teaching people? Otherwise, why do they seem to be better at creating more division versus offering education?

Perhaps that’s why many are suggesting that some type of change is needed.

What do you think?